Story originally published on May 16, 2011 by Global Post:

Story originally published on May 16, 2011 by Global Post:

SIDI BOUZID, Tunisia – It was the slap heard around the world.

When Mohamed Bouazizi, a 26-year-old fruit vendor from central Tunisia, was slapped by a female police officer on Dec. 17 last year, his pain was felt by millions of Arabs across North Africa and the Middle East.

Frustrated and humiliated after his entire livelihood — an unlicensed wooden cart and a few pounds of bananas — was confiscated, Bouazizi marched down to the local municipal building and lit himself on fire.

His self-immolation suicide sparked the popular uprising that eventually toppled then-President Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali, who fled Tunisia on Jan. 14 after ruling for over two decades.

Even before Bouazizi succumbed to his burn wounds in early January, he had already become a symbol of Tunisia’s revolution.

Bouazizi’s single act of protest proved that the fear barriers helping to prop up repressive regimes around the Arab world were collapsing, and provided the inspiration for millions of pro-reform activists from Tahrir to Tripoli.

“Who could have ever imagined any of this would ever happen?” asked Bouazizi’s grandmother Zara El Herchany, 91, who lived through French colonial rule in Tunisia and two subsequent dictatorial presidents. “Of course, we are all proud of him. He is a martyr.”

After Ben Ali’s ouster, the international media flocked to this small agricultural city in the heart of Tunisia to uncover the story of the famous “martyr,” whose name now adorns town squares and streets as far away as Paris.

Bouazizi’s compelling tale was told and retold across every medium, and will soon even be the subject of a major motion picture. That a single strike from a police officer could give rise to revolt across an entire region was the type of narrative legend that Hollywood producers only dream of.

But could it actually have been just a legend?

Some in Sidi Bouzid now believe it was. The town recently became divided after Bouazizi’s mother, who is regarded by some with suspicion, dropped the charges against the police officer who reportedly hit her son. Others doubt that Bouazizi was ever slapped in the first place.

“Mohamed Bouazizi is not our hero. He’s your hero,” said Nader Ncibi, 35, referring to the droves of foreign media who flooded his native Sidi Bouzid after Ben Ali’s departure and helped disseminate Bouazizi’s story.

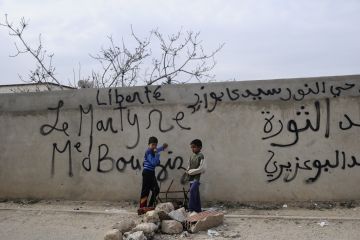

Bouazizi, however, was a hero in Sidi Bouzid at one point. Anti-regime graffiti memorializing the fruit vendor still defaces several concrete government buildings near the main square, which was later renamed in Bouazizi’s honor. A portrait of him hangs high above the city center on a gold-painted statue.

For many, Bouazizi will always be the local man who sparked a revolution against corruption, repression, and absolute power.

“Of course I respect and salute him for everything he did for all Tunisians,” said Gidri Badr el-Din, a 35-year-old resident of Sidi Bouzid.

But elsewhere, there are signs that Bouazizi’s legacy is in question.

Several images of Bouazizi that hung throughout the city have been torn down. A flagpole that was planted near his gravestone was ripped from the ground.

Some in Sidi Bouzid spitefully mutter, “Get out Mohamed,” a play on the popular chant that was directed at Ben Ali during the uprising, seemingly resentful of Bouazizi’s newfound fame.

At the roadside fruit market on the main street in Sidi Bouzid, Bouazizi’s former colleagues still debate the facts of his dispute with the police officer.

“He was never slapped,” said Monji Arabi, a fruit vendor who worked alongside Bouazizi and claimed to be present at the time.

Arabi is certainly not the only one who believes that — several eyewitnesses reportedly came forward and admitted that the slap never actually took place.

Some believe that Bouazizi may have started the quarrel with the policewoman, Fedia Hamdi.

In the weeks after the revolution, popular sentiment in town eventually started shifting away from Bouazizi, and residents began demonstrating in defense of Hamdi, who had been detained by Ben Ali in January to appease Tunisian protesters during the uprising.

Hamdi was released from jail in April, after Bouazizi’s mother Manoubia dropped the charges.

Manoubia, however, maintained her son’s story.

“It was a difficult decision,” Manoubia told Tunisian state media last month, but ending the case would ultimately help to begin the “reconciliation between the residents of Sidi Bouzid.”

Instead of uniting, many in town turned on Bouazizi’s mother after learning how much she had profited from her son’s death.

Manoubia accepted about $15,000 from Ben Ali before he was toppled, ostensibly as hush money to a family that was helping to stoke the flames of unrest.

She also received compensation from a prominent Tunisian film producer and several international news outlets seeking interviews, according to local media.

The residents’ anger, or envy, became more palpable after the Bouazizi family moved from working-class Sidi Bouzid to an upscale neighborhood just outside the capital city, Tunis.

Fame and fortune, complained residents of Sidi Bouzid, had changed a once modest woman.

“She started going on television and carrying herself with an air of superiority,” said Ammar Laffi, 54. “Who is she to act better than us? This town was where everything started — even more reason for the family to remain humble.”

Some of Bouazizi’s opponents may seem bitter. Most of the anger, however, stems from the fact that their tiny town — with its high poverty and rampant unemployment among youths — just lost the only reason it ever found its way onto the map.

And the many jobless residents of Sidi Bouzid worry that attention is fading when it is needed the most.

“People here still cannot find work, and the revolution is definitely not finished. But journalists stopped coming to Sidi Bouzid when his mother left. So who is going to tell our stories now?” asked Jamal Beyoaoui, a 37-year-old who said he had been unemployed “all his life.”

Only Bouazizi’s extended family seems excited at the prospect of fewer prodding journalists visiting town.

At the family’s cemetery on an unmarked plot on the outskirts of Sidi Bouzid, Bouazizi’s cousin lamented the fact that vandals had stolen the flag from his grave.

Hamouda Bouazizi, who is also unemployed, said he was shocked at the amount of torment he had received during job interviews in recent weeks — he was even considering changing his name.

Still, when asked about his cousin’s legacy, he echoed the one-word description etched above Mohamed Bouazizi’s name on his whitewashed gravestone: “a martyr.”

“I think people will remember him for doing a lot for our country,” said Hamouda Bouazizi. “But only God can judge him now.”