Story originally published on March 11, 2011 by Global Post:

Story originally published on March 11, 2011 by Global Post:

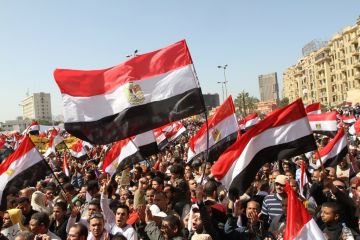

CAIRO, Egypt (GlobalPost) — Egypt’s revolution, it seems, is not over.

A week of violent clashes has underscored a growing perception among Egyptians that the regime they overthrew a month ago today is alive and well, working in the shadows to sow instability in a country scrambling to create the credible democratic institutions it has lacked for more than three decades.

The clashes on Wednesday that erupted in Tahrir Square — the epicenter of the protest movement that forced out Hosni Mubarak on Feb. 11 — reinforced suspicions that forces were at work trying to undermine the revolution.

Since Mubarak’s departure, hundreds of activists have continuously camped out in Tahrir Square to see through their demands for greater political reform. But some of Cairo’s residents said they were getting tired of the persistent demonstration.

“We’ve already changed the government. Now it’s time to get Egypt back to normal,” said Mohamed Hussein, 28, who was in Tahrir on Wednesday trying to convince the reformers to leave. “These protesters are just creating more traffic in Tahrir.”

Still, it had been rare for such disagreements to come to blows.

But on Wednesday, what started as a discussion quickly devolved into a violent clash as counter-protesters attacked the reformers. Both sides hurled rocks, bricks and small chunks of concrete at each other until the army arrived to break it up.

As dramatic as it was, it was only one of several instances of violence this week. On Tuesday, 13 people were killed and scores injured after fighting broke out between Muslims and Coptic Christians in a mostly Christian shantytown on the outskirts of Cairo.

The violence came as a surprise to those who had witnessed members of both religions overcome their differences to jointly call for regime change during the Egyptian uprising. Muslims and Christians famously prayed alongside one another in Tahrir Square before Mubarak’s departure.

Said Sadek, a sociology professor at the American University in Cairo, said that only agents from Egypt’s intelligence agency could be pitting these two sides against each other right now.

“State security is acting as a counter-revolutionary force,” he said. “Their tactics are to spread fear and chaos.”

Egyptian police forces began an uneasy return to work Thursday, adding to tensions in the capital and fears that those loyal to Mubarak could reappear at any time.

“The fact that all these things happen at the same time is really telling of the possibility of some sort of an organized campaign,” said Lina Attalah, editor of the independent Al-Masry Al-Youm newspaper’s English edition. “The identities of the perpetrators may be unknown, but it’s not hard to see some type of counter-revolutionary forces at work.”

The state security agency helped provide Mubarak with a legacy of stability during his three decades in power, often by using brutality to quiet the political opposition and rig elections. Egyptians now suspect that the recent unrest is a form of retaliation by security personnel who were angered by an earlier raid on the agency’s headquarters.

Last week, activists stormed the fortress-like building in search of evidence of torture and other human rights abuses. Eyewitnesses said they found devices used for torture, dank prison cells and countless roomfuls of both shredded and intact documents that could provide evidence of the regime’s brutal tactics.

Unverified, and possibly forged, documents allegedly taken from the building and posted online claim to be evidence of state security collusion in the planning of several internal terror attacks over the past decade, including a suicide bombing outside a church in Alexandria earlier this year.

Essam Sharaf, the country’s newly appointed prime minister, said he would not tolerate any forces of the “counter-revolution,” while pledging to bolster the police presence during his government’s first cabinet meeting.

Egypt’s military leadership has struggled in the last month to restore some semblance of stability to the country, which has a population of about 80 million, the largest in the region. But elections are scheduled and at least two darlings of the reform movement, Amr Moussa and Mohamed Elbaradei, have thrown their hat into the ring. Moussa held a raucous, American-style town hall meeting earlier in the week.

The persistent unrest, however, and the threat posed by those still loyal to Mubarak, has underlined just how far Egypt still has to go before democracy can really begin to take hold.

“Their goal is to make people realize that under dictatorship, there was more peace than under democracy,” Sadek said about the so-called counter-revolutionary forces.